Mondrian White on White Pivotal Set, Oompa Loompas, A Buzz and Holler,plus Racks of Disemboweled Cadavers. LOVELY

Texas Tech’s Mother Courage, April 29 | First Performance | A slanted critical review of sorts

As I squirmed in my seat for three hours, fifteen minutes, my anticipation and pleasure resided in what occurred between scenes, which began each time with a buzz, and holler that activated Oompa Loompas to reposition the set. Providing mid-scene intrigue were the racks of disemboweled cadavers with their dangling entrails.

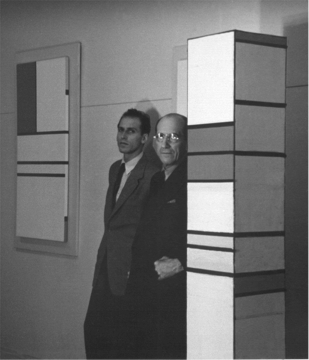

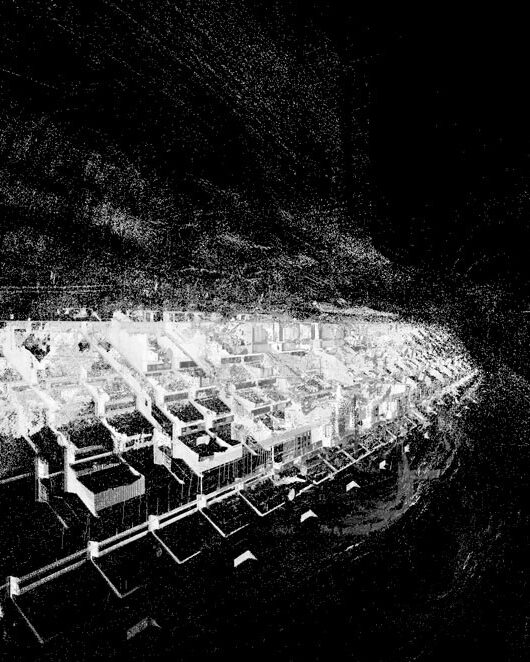

The white portable set (below. figure 1) was like modernist geometric painting including extreme color reduction. It called to mind Kazimir Malevich’s 1918 painting, White on White (figure 2), and his contemporary’s, Piet Mondrian, paintings and spatial forms (figure 3). The play’s set was modularly built into columns with 4×4 footprints and heights ranging from 10 to 16 feet. Though not visible, their base included wheels, allowing for quick almost Tetris-like repositioning. Each column included a door-sized passage, but like the wheels, they were kept out of audience view. The interiors were lined with white non-reflective fabric so if per chance the passage were slightly exposed to the audience, it would go unnoticed. These passages functioned to hide stagehands that would mid-scene provide characters with prop and mics.

figure 3: Mondrian

The neutral white and geometric simplicity diminished scenic distractions so that the plays action was perceptually foregrounded. It also reduced the need and risks in replication or accuracy of the temporal and geographical setting. In fact, it decontextualized the play from the early seventeen hundreds scripted setting. The only ground to situate the viewer in the temporal location was the design of the costumes and key props.

In the decontextualized space, the repositioning of the columns indicated scene changes. With each shift, various flat panels, reminiscent of the columns’ Mondrian-like surfaces, were lowered from the ceiling to further reshape the space, as a sign to cue scenic change. The transitions were made in full audience view. Despite the physical repositioning, it was each scene’s action that dictated how the space should be interpreted—pub or pasture, day or night, plus indicating Mother Courage’s migratory habit. I found the set and its repositioning aesthetically soothing. It counterbalanced the emotive connotations associated with theatrically required projections of voice and gesture.

The play would have been significantly served by decontextualizing it beyond just the white set to release its primary read from being tethered to seventeen hundreds. Converting all the costuming and props to white with the exception of each characters vest, sash or a single item of distinction, while maintaining their antiquated design, would have effectively diminished the chronological anchor. This would have emphasized the characters’ actions and script in ways that would transcend the time period becoming more applicable for today. It would correlate the plot in terms of our own cultural and global climate with its dragged out “incursions,” leftovers of our War on Terror, and other political interventions. Only in unpacking the play for this paper has the probable intention of the director’s selection of Mother Courage revealed real correlations.

Raytheon, a weapons guidance system corp, is a most profitable stock. I shall neither confirm nor deny that I may own some. Perhaps it has even assisted in temporarily freeing me to pursue my PhD. Am I equally complicit and compromised by the benefits of war, as Mother Courage was? Do I stand on carcasses of others as I reach for yet another degree? Had the play more clearly de-tethered from its historical fix, I would have arrived at the uncomfortable position that reveals me as part of our contemporary war economy. This would have been quite poignant because it would turn my harsh judgment of Mother Courage around on myself. I like to be unsettled, moved from my willful blindness and American arrogance. I wish the play itself had done this for me, it did not. I maintain my buffered ego and denial. Plus perhaps I also bought Tesla stock when it first hit the market. Ha. Apparently, I am into clean energy and bombing, just call me Mother Courage.

It would be perfect to end this post at the last line, but then I would have to re-title it. I ramble on with the review for class criteria hoop jumping and to get to the Oompa Loompas, the play’s best part ☺. But first a little more on the set. The drop down paintings as contextual staging were problematic. The only painting that assisted the play in terms of progressing the story was the replica of Goya’s painting, May Third. The first and last paintings where exceptionally disruptive—perceptually fixating. The first glowed neon orange—visually eye riveting, screaming. The last was a gargantuas muddy brown blob OZ head. Its scale made it impossible to ignore. I assume, though unrecognizable to me, it referenced a historical painting, but it was just shit ugly and distracted me from the story.

On the other hand, I loved the clothes racks packed with cadaverous heads and their disemboweled torsos with dangling entrails. Then again, perhaps I own Raytheon stock. Sigh. In a manner, the cadavers correlated with the staging in that they decontextualized the play from the “real” and its temporal location in history. The clothing store-like racks linked the story to contemporary culture, perhaps pointing to the costs of our consumer-based economy. I appreciated the way the abstraction and repetition suggested the horrors and carnage of war with the multiple racks signaling ongoing death counts.

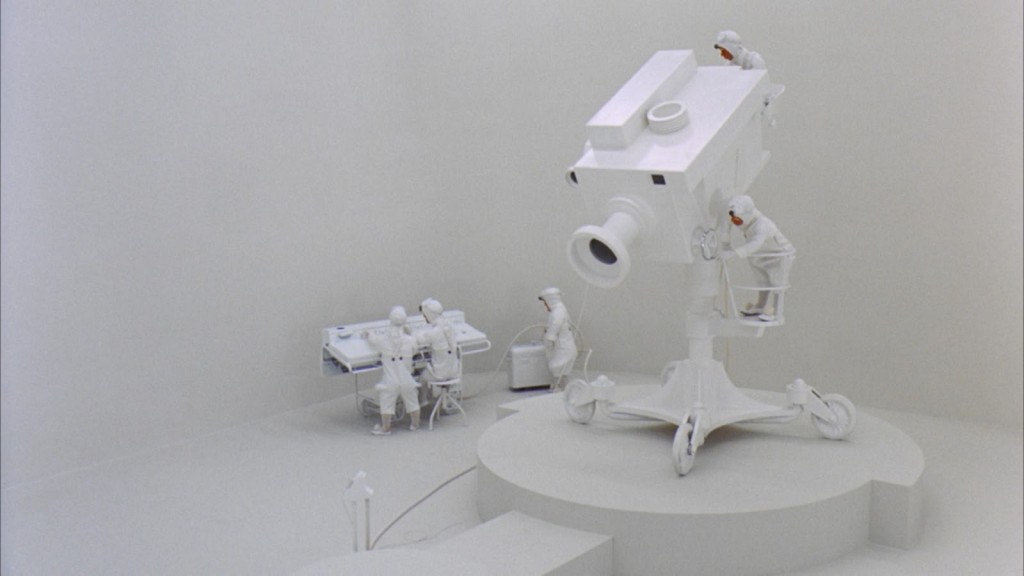

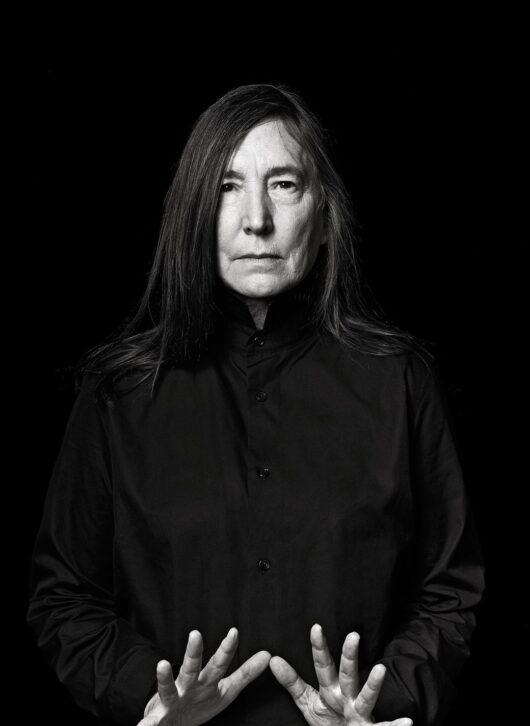

The acting and singing left me wanting. As fine an actress as Mother Courage was, she was not even remotely my favorite character. The very best thing about the play was the Oompa Loompas, apparently recast from Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. Though neither short nor bearded, they dressed hygienically, donned in all white paper industrial-like coveralls, including white foot booties that muffled the sound of their walking. They functioned between scenes, just as they did in the movie when cued by Wonka and set to the task of scene transition by rolling off the Blueberry Girl for squishing or the other “bad” children for obvious consequences.

Likewise, in Mother Courage, a buzzer, followed by a holler, “scene change,” activated the scenic inbetweens. The Oompas moved silently with calculated intent as they danced the white columns to new positions. It was just freaking beautiful. The music played softly in accompaniment, but I was so fixate on their coordination and efficient movements it really didn’t register. I would have been happy with three hours of that or at least twenty-two minutes. In either case, I would need a hint of a conceptual intent. Seriously, I might have preferred the play’s narrative without bodily action. With the characters garbed in white costume, proplessly standing behind a series of white podiums, lined up in a row, voicing their lines. And then holding still and silent as the Oompa Loompas, initiated with the buzzer and pre-emptive holler, “scene change,” did their thing. Even with unaltered script, this would have teleported the viewer from the past to the future of now. Oh, I would have been so engaged. Sometimes “less is more” though that would require a butt-load of risk and courage.

Ha, and would the Oompa Loompas songs be relevant to Brecht’s script? I think so. It is worth a test, in creating a new version of Mother Courage worth doing.

NOTE: Perhaps interdisciplinary in development, Mother Courage seemed to fit my stereotype of conventional three parts play and one part musical.

0